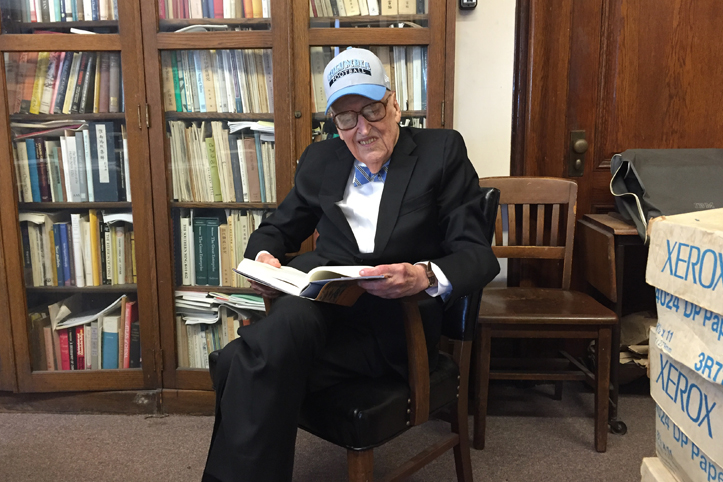

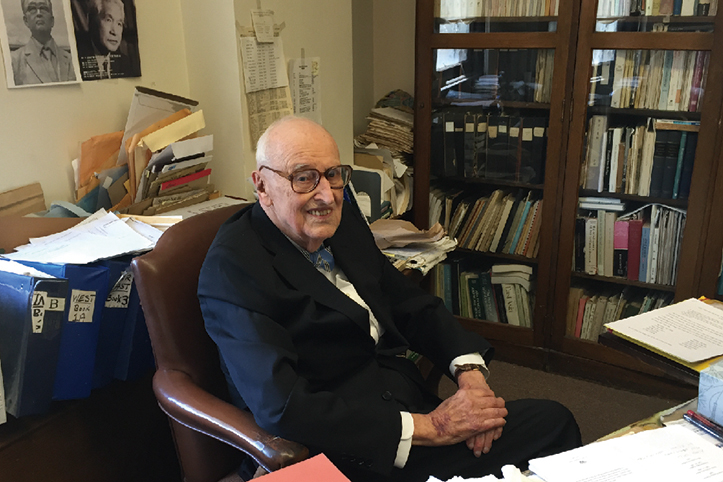

Born in 1919, Professor William Theodore de Bary is a pioneering scholar in the field of Confucian intellectual history. Upon completing his doctoral degree in 1953 at Columbia University, he started his teaching and research career at his alma mater as a specialist in Chinese intellectual history, especially focusing on Confucianism, and has since continued on even after his retirement in 1990. Recognized as essentially creating the field of Neo-Confucian studies in North America, he has written and edited over 30 books with many of them making groundbreaking contributions to the study of Confucianism. He chaired the Department of East Asian Languages and Culture between 1960 and 1966 and served as Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs and Provost from 1971 to 1978. He was also President of the Association of Asian Studies from 1969 to 1970. Even now in his nineties, he continues to publish works that reflect his commitment to addressing key questions that face humanity, including his 2013 publication The Great Civilized Conversation: Education for a World Community.

Professor de Bary’s study of Confucianism began with Huang Zongxi’s Waiting for the Dawn, through which he strove to understand internal problems China faced through its history, ideals and traditions, free from Western preconceptions, theories, and values. With his leading insight into the field, Professor de Bary went on to pioneer the field of Neo-Confucianism beginning with his 1953 publication of “A Reappraisal of Neo-Confucianism.” He does not champion traditional Confucian thought as perfect; instead, he endeavors to bring forth the Confucian idea and ideal of daotong or what he phrases as “the reconstitution of the Way.”

Over the past half a century, Professor de Bary’s masterpieces had centered around two major themes. The first being the discussion of the history and evolution of the Cheng-Zhu school of Neo-Confucianism through a historical perspective as seen in his representative works Neo-Confucian Orthodoxy and the Learning of the Mind-and-Heart (1981) and Message of the Mind in Neo-Confucianism (1989). His second major theme focuses on the Confucian emphasis on the individual and freedom, advocating that Confucianism is by no means an obstacle to modernization and is instead the core foundation of culture across East Asia. In particular, he is especially interested in Wang Gen and Li Zhi’s focus on the individual, which he delves into in The Liberal Tradition in China (1982). He stresses that while China lacks what in the West is known as “liberalism,” this does not mean China does not value freedom. His research demonstrates that Neo-Confucian teachings in late imperial China, particularly during the Ming Dynasty, contains values that he terms “liberal tendencies.” And throughout history, these values are propelled by Confucian and Neo-Confucian scholar-officials, who Professor de Bary regards as noble junzi (gentlemen) with a “prophetic voice” that are willing to take a stand against the abuse of political power. In his 1990 publication Learning for One's Self: Essays on the Individual in Neo-Confucian Thought, he has found common ground between the Eastern Confucian cultivation of the self and the Western emphasis on individualism.

Despite his great respect for Confucianism, Professor de Bary understands that the “liberal tendencies” and “prophetic voices” in Confucian tradition have never been transformed into legal institutions such as those in Western liberal democracy to protect basic civil rights. The Trouble with Confucianism fully examines this dilemma and limitation and advocates that an understanding of why Confucian political ideas failed to take hold must be based on the ideals set forth by the tradition itself. The Confucian ideal of cultivating sage kings is difficult to realize and must rely on junzi to mediate between the ruler and the people. While junzi are “destined” to serve as the “spokesmen of heaven,” they are unlike the Western prophet who has been ordained as the messenger of God. The biggest limitation of the “prophet” tradition in China is that it lacks the power base of an authority like the Western church. However, the most significant limitation is how far removed the junzi are from the people in that they only serve to convey messages to the ruler rather than the people.

Professor de Bary is also concerned with the democratic values of the East and the West, which he discusses when examining Huang Zongxi’s Waiting for the Dawn. In 1993, his English translation of this book provides a lengthy introduction. He believes that the elements of democracy in Huang Zongxi’s work cannot be directly transplanted into Western democracy. The purpose of Huang’s advocacy of Confucian constitutionalism is to increase the authority of the prime minister so he can serve as a check and balance against the monarchy. The establishment of an education system as a forum for educated opinion on public affairs is another check against the monarchy. However, Huang’s ideal political system and the Western representative democracy have fundamental differences: The prime minister in the East is selected by the emperor and public opinion should be driven by scholar-officials. Professor de Bary finds Waiting for the Dawn of particular significance because this work places much emphasis on law as an outgrowth of local needs and not imposed by leaders with a political agenda. Huang’s political tract condemns laws driven by political agendas and advocates for the importance of creating laws before the selection rulers. This perspective departs from the traditional Confucian expectation of monarchs. Nevertheless, Professor de Bary also understands that Huang’s legal system does not resemble that of the social contract of the West, so the role of the people is greatly limited.

In recent years, Professor de Bary has turned his focus to a comparative study of Western and Eastern civilization and their areas of compatibility. In 2004, he published Nobility and Civility: Asian Ideals of Leadership and the Common Good, where he propounds that utilizing only a Western perspective as a compass for civilization is not in line with multiculturalism. The East has a long history of independent traditions and will not follow the Western model of development. Besides pointing out the vibrant history of Confucian and Indian traditions, Professor de Bary also holds an open and multicultural outlook, where he encourages a dialogue between different cultures as a way to find common ground and the best way to showcase the value of human rights of civil society and resolve key issues facing the world today. Confucian teachings of “restraining oneself” and “the Way and its relationship to all things” still apply today. Published in 1988, East Asian Civilizations: A Dialogue in Five Stages analyzes the development and exchanges within East Asian civilization and offers the key suggestion of encouraging dialogue and exchange between different cultures and civilizations. Professor de Bary believes that in a chaotic world, there is no other better remedy, and this has been the purpose of his scholarship.

Besides his scholastic achievements, Professor de Bary has headed many academic projects including the translation and compilation of various texts. Students and scholars in the field of East Asian studies have all greatly benefited from his 1960’s Sources of Chinese Tradition, in which he has translated and annotated a vast number of Chinese classics and texts. This key publication offers a thorough portrayal of different aspects of Chinese social, political, intellectual, and cultural traditions to the English-speaking world. The continual publication of much enlarged editions of this work in 1999, 2000, and 2004 is a testimony to the significant contribution this sourcebook has made to Sinology. He has also been a leading figure presiding over the translation of Eastern classics at Columbia University, a project that has seen the translation of over 150 classics, which serves as a key foundation for East Asian studies in the West. He has also invited leading scholars from around the world to dialogue and exchange findings on Neo-Confucianism, publishing their insights for readers around the world.

Overall, Professor de Bary has fostered a global conversation based on the common values and experiences shared by the East and the West, serving as a bridge between Confucian traditions and the modern world. As such, he is a rare exemplar of a scholar known not only for his monumental scholarship and leadership in the field of Confucianism but also for his unflagging dedication to renewing and realizing a great civilized conversation to iron out differences and foster mutual understanding between the East and the West.