Since the late 1950s, Wang Gungwu (1930- ) has been publishing pioneering works on the history of imperial China, China and Southeast Asia, and changing identities of Chinese in Southeast Asia. He also served as the teacher and mentor of several generations of scholars in the field. Born in Surabaya in the Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia) to patriotic, scholarly Chinese parents, and educated in British Malaya and London, he grew up as an insider both in Chinese Confucian culture and in the finest British academic tradition. His subsequent brilliant academic career in Malaya, Australia, Hong Kong, and Singapore, however, inevitably defines him as an “outsider” in the interpretation of China’s view of the world. This unique vantage point affords the most valuable and distinctive insights on Chinese history that characterize many of his works, and distinguishes him as one of the most original and inspiring historians of our times. As eloquently pointed out by William Skinner in 1982, Wang Gungwu embodies three scholarly personae, “The sinological historian, the pundit of Malaysian affairs, and the expert on the Nanyang Chinese.”

Sino-centric World Order: Changing Visions of Tianxia (天下)

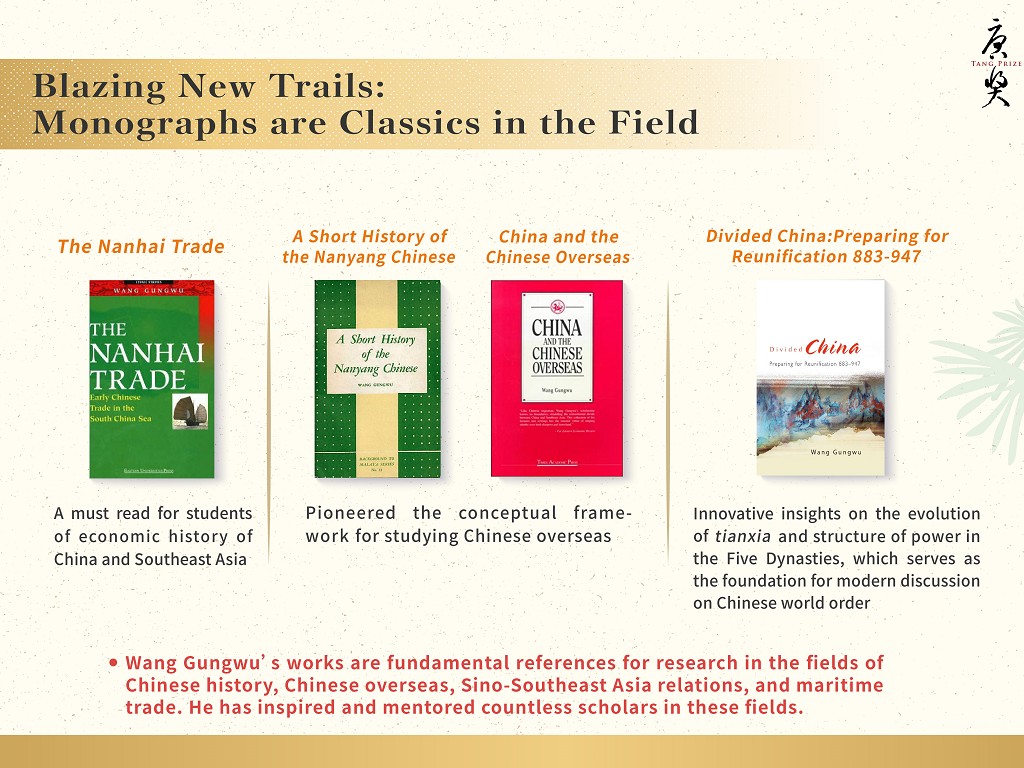

Wang Gungwu’s doctoral dissertation (SOAS, London, 1957) published in 1963, The Structure of Power in North China during the Five Dynasties, was his first study on the Chinese world order from a northern perspective. He viewed imperial China as projected by the classics as the world of the Yellow River, where core ideas and values have emerged from the interactions between the plains of Hebei, Henan, and Shandong, and the uplands of Shanxi and Shaanxi, the cradle zones of Chinese civilization, whereas the southern kingdoms of the same period remained politically and culturally marginalized. This early study of a divided Chinese empire drew Wang Gungwu’s attention to rare historical periods of North/South unification into a common tianxia as interludes of political greatness, an ideal aspired by all rulers of China (Divided China: Preparing for Reunification, 883-947, 2007). His early research set the stage for his later studies on modern Chinese history, especially those on the Republican and the Communist Revolutions in 1911 and 1949, respectively, seen by him as modern attempts to realize the old dream of re-unifying China.[1]

His recent publications focused more specifically on what he sees as a probable “fourth rise” of China since 1978, an emerging modern tianxia envisioned not entirely in the old imperial tradition, but one that will be based on new shared values that create a sense of national belonging, while not upsetting the current world order. A recent book based on his interviews, Eurasian Core and Its Edges: Dialogues with Wang Gungwu on History of the World (Ooi Kee Beng, 2015), has certainly spark animated discussions by both historians and political scientists on the opportunities and challenges that China is facing in its advance towards the “fourth rise.”

China’s South

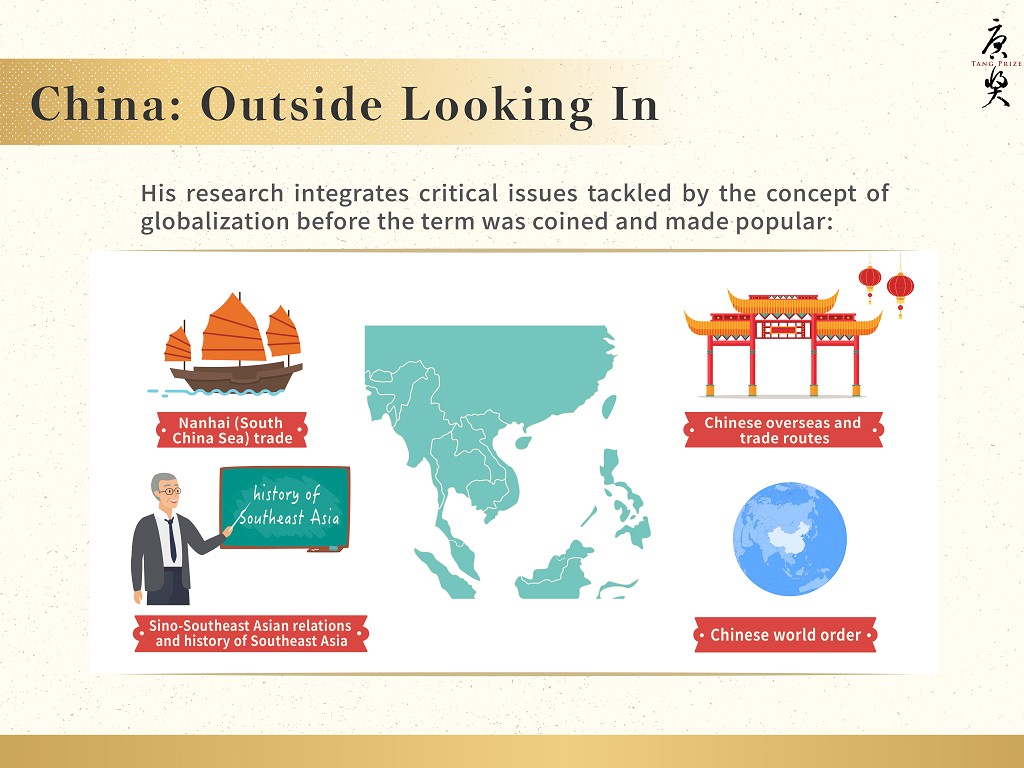

Wang Gungwu’s original approach to understanding China from the southern perspective is in part a natural choice given his personal experience, and also a development of his early interest on Chinese trade in the southern seas (“The Nanhai Trade: A Study of the Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea,” M.A. thesis, University of Malaya, 1954). The classical Chinese education he had at home as a child and his doctoral study in London taught him about the northern origin of the Chinese civilization; his growing up in Malaya arose his early interest on Sun Yat-sen, and the Republican revolution made him sensitive to the political impact of the masses of southern Chinese in Southeast Asia—a historical fact that historians of his time paid little attention to.

In a brilliant lecture he gave at the University of Hong Kong in November 2018 (“China’s South: Changing Perspective”), Wang Gungwu explained that, while southern literati elite of the northward looking Ming/Qing regimes acquired prestige and political influence in the north, their non-elite compatriots—traders, peasants, fishermen—were increasingly attracted to wealth-making possibilities in the South China Sea. The northern political regimes were traditionally wary of military assaults by enemies coming overland from the north but unaware of existential threats from the maritime south, until the mid-19th century. In other words, the commercial opportunities of the southern maritime global network, and the threat that came with it, were understood by common people in China’s south for a long time, well before the political elite, who recognized the peril when it was too late. Wang Gungwu connects this history to China’s present by pointing out that while China’s southern maritime outreach has clearly become central to the nation’s future economic development, as shown by the One Belt One Road initiative, potential conflicts with Southeast Asian nations have yet to be understood and properly dealt with.

His mastery of the geopolitical significance of China’s south and Southeast Asia greatly impressed John Fairbank as early as the 1960s when he was invited to contribute to The Chinese World Order (1968), a volume that Fairbank was editing at the time (“Early Ming relations with Southeast Asia – a background essay”). After decades of research on Chinese in Southeast Asia, he recently re-focused and further sharpened his views on this specific topic in a new book that has certainly aroused much public interest: China Reconnects: Joining a Deep-rooted Past to a New World Order (2019, parts reprinted from his 2018 lecture).

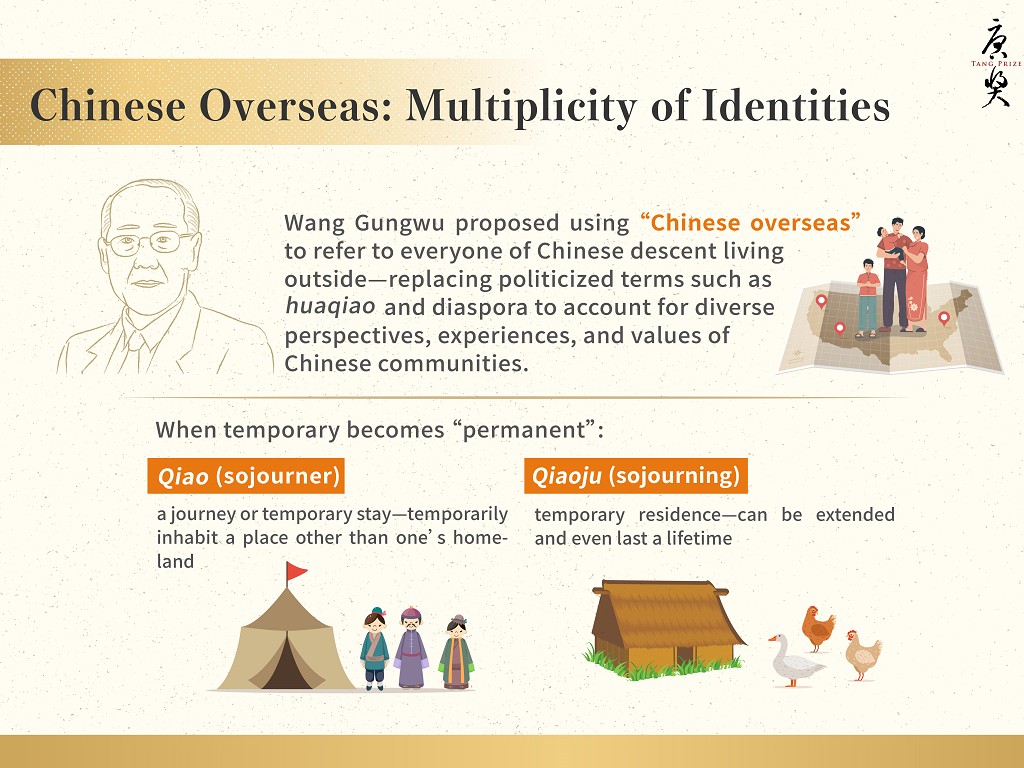

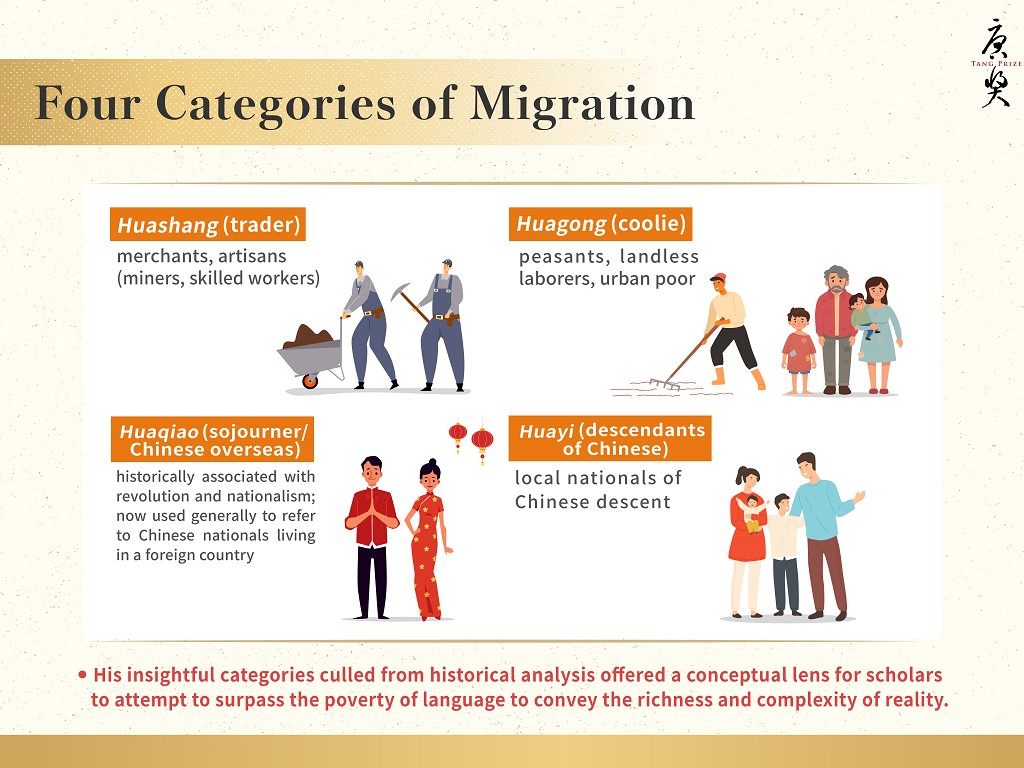

Chinese in Southeast Asia: Multiplicity of Identities

Wang Gungwu is best known for his pioneering work on Chinese in Southeast Asia. He does not see the “Chinese” in this part of the world as a monolithic group with a clear identity with China. By looking at their place of origin (from northern or southern China with different deities and cultural practices), the historical moment of their migration from China, their economic activities, and their integration into their host nation states, he distinguishes different historical processes constructing various types of “Chineseness” that these communities could assert when engaging their country of residence or mainland China.

He stresses the key factor of postcolonial nation-building in Southeast Asia that created political identities adopted by its citizens of multi-ethnic origins, including the Chinese. The cultural identity of ethnic Chinese, or their Chineseness, does not exclude their national identity with their host country. He advocates that the Chinese overseas be studied in the context of their respective national environments, and taken out of a dominant China reference point. Chinese overseas today, with a complex identity, are no longer the same as their forefathers who left China as huaqiao (Chinese sojourners) with a single and dominant Chinese identity during the Qing until the early 20th century, when they played a key role in creating modern Chinese nationalism.[2]

His many books written with first-hand life experience and erudition on Southeast Asian history, and sophisticated analysis of the role of Chinese in the region past and present, are now classics in the field: These include A Short History of the Nanyang Chinese, 1959; Community and Nation: Essays on Southeast Asia and the Chinese 1981; Southeast Asia and the Chinese, 1987; The Nanhai Trade: The Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea (南洋貿易與南洋華人, 1988); China and the Chinese Overseas, 1991; Community and Nation: China, Southeast Asia and Australia, 1992; The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy, 2000; Don’t Leave Home: Migration and the Chinese, 2001; Overseas Chinese Studies: New Horizon and Direction—Collected Essays by Professor Wang Gungwu (海外華人研究的大視野與新方向, 2002); China and its Cultures: From the Periphery (離鄉別土: 境外看中華, 2007).

*******

In addition to his pioneering studies on China and Chinese and Southeast Asia, Wang Gungwu has also written important works on contemporary Chinese politics and economy, imperialism and post-colonialism in Southeast Asia, and on the history of Malaysia more specifically. His extraordinary publication record started in 1953 and continues until 2019, with hardly any blank year.

On top of his brilliant scholastic achievement, he has also been a model academic leader: He was Head of Department (1968-1986) and Director of the Research School of Pacific Studies (1975-1980) at Australian National University; Vice President (President) of the University of Hong Kong, 1986-1995; Chairman, Institute of East Asian Political Economy, Singapore, 1996-2002; Director of East Asian Institute of National University of Singapore, 1997-2007.

Wang Gungwu as a scholar is widely respected and admired, as shown by the many honors he has obtained: Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities (1971); Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1991); Academician of Academia Sinica (1992); Winner of the international Fukuoka Asian Cultural Prize (1994); Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Science (1995); Honorary Doctorate of Letters from the University of Hong Kong (2002); University Professor, National University of Singapore (2007); Honorary Doctorate of Letters from the University of Cambridge (2009); Economic and Social Science Prize, Asia Cosmopolitan Award (2014).

For his outstanding contributions and achievements, Wang Gungwu is awarded the 2020 Tang Prize in Sinology.

[1] For detailed treatments of these topics, please see Wang Gungwu’s publications on China and the World since 1949: The impact of Independence, Modernity and Revolution (1977), The Chinese Way: China’s Position in International Relations (1995), and Joining the Modern World: Inside and Outside China (2000).

[2] For more, see Wang Gungwu’s The Chineseness of China (1991) and Diasporic Chinese Ventures: The Life and Work of Wang Gungwu (2004).

Position

University Professor, National University of Singapore

Date of Birth:1930.10.09

Place of Birth:Born in Surabaya, Java (now Indonesia)s

Nationality:Australian Citizen

Field of Specialization:History

Education

1957 Ph.D., School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

1954 M.A. , University of Malaya

1953 B.A. , University of Malaya

Main Professional Experience

- University Professor, National University of Singapore (2007- )

- Professor and Director, East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore (1997-2007)

- Professor and Head, Department of Far Eastern History (1968-1986), Director, Research School of Pacific Studies (1975-1980), Emeritus Professor (1988), Australian National University

- Professor and Head of Department of History (1963-1968), University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur

- Assistant Lecturer, Lecturer, Senior Lecturer, Dean of the Faculty of Arts, University of Malaya, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur (1957-1963)

- Visiting Appointments: Rockefeller Visiting Fellow, University of London; All Souls College Visiting Fellow, Oxford University; John A. Burns Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Hawaii; Rose Morgan Visiting Professor, University of Kansas

Academic & Administrative Service (selected)

- Chairman of Governing Board, East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore (2007-2018)

- Chairman of Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (2004-2017)

- Chairman of Board of Trustees, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore (2002-2019)

- Chairman, Institute of East Asian Political Economy, Singapore (1996-1997)

- Vice-Chancellor (President), University of Hong Kong (1986-1995)

- President of the Australian Academy of the Humanities (1980-1983)

Academic Awards and Honors (selected)

- Recipient, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Award for Distinguished Contributions to China Studies (2018)

- Officer of the Order of Australia (AO 2018)

- Recipient, Economic and Social Science Prize, Asia Cosmopolitan Awards (2014)

- Recipient, Darjah Dato’ Paduka Mahkota Perak, Malaysia (DPMP 2011)

- Recipient, Distinguished Service Award, National University of Singapore (2005)

- Recipient, Public Service Medal (PBM 2004), Public Service Star Award (BBM 2008), Meritorious Service Medal (PJG 2013), Government of Singapore

- Recipient, Fukuoka Asian Cultural (International Academic) Prize (1994)

- Academician, Academia Sinica (1992-)

- Commander of the British Empire (CBE 1991)

- Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities (1971)

- Honorary Memberships: Foreign Honorary Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1995); Honorary Research Member, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (1996); Honorary Fellow, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (1996); Honorary Fellow, Wolfson College, University of Cambridge (2009)

- Honorary Professorships: Peking University, University of Hong Kong, Fudan University, Nanjing University, Tsinghua University, Jinan University, Xian Jiaotong University, China Foreign Affairs University

- Honorary Doctorates: University of Hong Kong, University of Sydney, Australian National University, University of Melbourne, Monash University, Griffith University, University of Hull, Soka University, University of Cambridge

Publications (selected)[1]

English monographs

- The Nanhai Trade: The Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea. Singapore: Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1958; Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1998.

- A Short History of the Nanyang Chinese. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 1959.

- The Structure of Power in North China During the Five Dynasties. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1963; Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1967.

- China and the World Since 1949: The Impact of Independence, Modernity, and Revolution. London: Palgrave Macmillan; New York: St Martin’s Press, 1977.

- Community and Nation: Essays on Southeast Asia and the Chinese, selected by Anthony Reid. Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) Ltd., 1981.

- China and the Chinese Overseas. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991; Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2003.

- The Chineseness of China: Selected Essays. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Community and Nation: China, Southeast Asia and Australia. New South Wales: Allen & Unwin, 1992.[2]

- The Chinese Way: China’s Position in International Relations. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1995.

- China and Southeast Asia: Myths, Threats and Culture. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company and Singapore University Press, 1999.

- The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Joining the Modern World: Inside and Outside China. Singapore: Singapore University Press and World Scientific Publishing Company, 2000.

- Only Connect! Sino-Malay Encounters. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 2001; Singapore: Eastern Universities Press: 2003.[3]

- Don't Leave Home: Migration and the Chinese. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 2001; Singapore: Eastern Universities Press: 2003.

- To Act is to Know: Chinese Dilemmas. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 2002; Singapore: Eastern Universities Press: 2003.[4]

- Bind Us in Time: Nation and Civilisation in Asia. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 2002; Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2003.

- Anglo-Chinese Encounters Since 1800: War, Trade, Science and Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Ideas Won't Keep: The Struggle for China's Future. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2003.[5]

- Diasporic Chinese Ventures: The Life and Work of Wang Gungwu, edited by Gregor Benton and Liu Hong. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004.

- Divided China: Preparing for Reunification, 883-947. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2007.[6]

- Renewal: The Chinese State and the New Global History. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2013.

- Another China Cycle: Committing to Reform. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2014.

- Ooi Kee Beng, The Eurasian Core and Its Edges: Dialogues with Wang Gungwu on the History of the World. Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies, 2015.

- Nanyang: Essays on Heritage. Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies, 2018.

- Home Is Not Here. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2018.

- China Reconnects: Joining A Deep-rooted Past To A New World Order. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2019.

- Home Is Where We Are, co-authored with Margaret Wang. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2020.

English edited volumes

- Malaysia: A Survey, edited by Wang Gungwu. Singapore: Donald Moore Books Ltd; London: Pall Mall Press; New York: Fredrick A Praeger; Melbourne: F W Cheshire, 1964.

- Essays on the Sources for Chinese History, co-edited with Donald D. Leslie and Colin Mackerras. Canberra: Australian National University Press; Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1973.

- Self and Biography: Essays on the Individual and Society in Asia, edited by Wang Gungwu. Sydney: Sydney University Press for the Australian Academy of the Humanities, 1975.

- Hong Kong: Dilemmas of Growth, co-edited with Chi-keung Leung and Jennifer W. Cushman. Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University; Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 1980.

- Society and the Writer: Essays on Literature in Modern Asia, co-edited with Milagros Guerrero and David Marr. Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, the Australian National University, 1981.

- Changing Identities of the Southeast Asian Chinese since World War II, co-edited with Jennifer W. Cushman. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1988.

- Hong Kong's Transition: A Decade After the Deal, co-edited with Wong Siu-lun. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Global History and Migrations, edited by Wang Gungwu. Boulder: Westview Press, 1997.

- Hong Kong in the Asia-Pacific Region: Rising to the New Challenges, co-edited with Wong Siu-Lun. Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 1997.

- Dynamic Hong Kong: Business and Culture, co-edited with Wong Siu-lun. Hong Kong: The Centre of Asian Studies, the University of Hong Kong, 1997.

- The Chinese Diaspora: Selected Essays, Volumes I and II, co-edited with Wang Ling-chi. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1998.

- China’s Political Economy, co-edited with John Wong. Singapore: Singapore University Press and World Scientific Publishing Company, 1998.

- Hong Kong in China: The Challenges of Transition, co-edited with John Wong. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1999.

- China: Two Decades of Reform and Change, co-edited with John Wong. Singapore: Singapore University Press and World Scientific Publishing Company, 1999.

- Towards A New Millennium: Building on Hong Kong’s Strengths, co-edited with Wong Siu-lun. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1999.

- Reform, Legitimacy and Dilemmas: China's Politics and Society, co-edited with Zheng Yongnian. Singapore: Singapore University Press and World Scientific Publishing Company, 2000.

- Damage Control: The Chinese Communist Party in the Jiang Zemin Era, co-edited with Zheng Yongnian. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2003.

- Sino-Asiatica: Papers dedicated to Professor Liu Ts’un-yan on the Occasion of His 85th Birthday, co-edited with Rafe de Crespigny and Igor de Rachewiltz. Canberra: Faculty of Asian Studies, Australian National University, 2003.

- The Iraq War and its Consequences: Thoughts of Nobel Peace Laureates and Eminent Scholars, co-edited with Irwin Abrams. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2003.

- Maritime China in Transition 1750–1850, co-edited with Ng Chin-keong. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2004.

- Nation-Building: Five Southeast Asian Histories, edited by Wang Gungwu. Singapore: ISEAS Publications, 2005.

- Interpreting China’s Development, co-edited with John Wong. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2007.

- China and the New International Order, co-edited with Zheng Yongnian. New York: Routledge, 2008.

- Voice of Malayan Revolution: The CPM Radio War against Singapore and Malaysia, 1969-1981, co-edited with Ong Weichong. Singapore: S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 2009.

- China: Development and Governance, co-edited with Zheng Yongnian. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2013.

English festschrifts

- Power and Identity in the Chinese World Order: Festschrift in Honour of Professor Wang Gungwu, edited by Billy K. L. So, John FitzGerald, Huang Jianli and James K. Chin. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2003.

- China and International Relations: The Chinese View and the Contribution of Wang Gungwu, edited by Zheng Yongnian. London and New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Junzi: Scholar-gentleman, in Conversation with Asad-ul Iqbal Latif. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2010.

- Wang Gungwu: Educator And Scholar, edited by Zheng Yongnian and Phua Kok Khoo. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2012.

- Chineseness and Modernity in a Changing China: Essays in Honour of Professor Wang Gungwu, edited by Zheng Yongnian and Zhao Litao. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2020.

Chinese (provided in Chinese for ease of locating publications)

- 《南洋華人簡史》(A Short History of the Nanyang Chinese),張益善譯註。臺北:水牛圖書出版,1969。

- 《東南亞與華人:王賡武教授論文選集》(Southeast Asia and the Chinese),姚楠編譯。北京:中國友誼出版公司,1987。

- 《南洋貿易與南洋華人》(Nanhai Trade and Nanyang Chinese),姚楠譯。香港:中華書局,1988。

- 《歷史的功能》(The Use of History),姚楠編譯。香港:中華書局,1990。

- 《中國與海外華人》,(China and the Chinese Overseas)天津編譯中心譯。香港:商務印書館,1994。

- 主編,《香港史新編(全二冊)》(Hong Kong History: New Perspectives),香港:三聯,1997、2017。

- 劉宏主編,《王賡武訪談與言論集:坦蕩人生、學者情懷》(The Life of a Scholar: Professor Wang Gungwu's Interviews and Speeches),River Edge, NJ:八方文化企業,2000。

- 劉宏、黃堅立主編,《海外華人研究的大視野與新方向:王賡武教授論文集》 (Overseas Chinese Studies: New Horizons—Collected Essays by Professor Wang Gungwu),River Edge, NJ:八方文化企業,2002。

- 《王賡武自選集》(Selected Works of Wang Gungwu),上海:上海教育出版社,2002。

- 選編,《王宓文紀念集》(Wang Fo-wen, 1903–1972: A Memorial Collection of Poems, Essays and Calligraphy),River Edge, NJ:八方文化企業,2002。

- 王賡武、宮少朋主編,《伊戰啟示錄》(Revealing Iraq),新加坡:八方文化企業,2003。

- 《移民及興起的中國》(Migrants and the Rise of China) 新加坡: 八方文化企業,[7]

- 《離鄉別土:境外看中華》,(China and Its Cultures: From the Periphery)臺北:中央研究院歷史語言研究所,2007。

- 王賡武、鄭永年主編,《中國的主義之爭:從五四運動到當代》(China's Ideological Battles since the May Fourth Movement)。新加坡: 八方文化企業,2009。

- 黃賢強主編,《族群、歷史、文化:跨域研究東南亞和東亞──慶祝王賡武教授八秩晉一華誕專集(全二冊)》(Ethnicity, History and Culture: Trans-Regional and Cross-Disciplinary Studies on Southeast Asia and East Asia. In Honour of Wang Gungwu on his 81st Birthday)。新加坡:八方文化創作室、新加坡國立大學中文系,2011。

- 《華人與中國:王賡武自選集》(The Chinese and China),姚楠、張洪彬、黃啟江、倪華強等譯。上海: 上海人民出版社,2013。

- 《五代時期北方中國的權力結構》(The Structure of Power in North China During the Five Dynasties),胡耀飛、尹承譯。上海:中西書局,2014。

- 《十九世紀以來的中英相遇:戰爭、貿易、科學與管治》(Anglo-Chinese Encounters Since 1800: War, Trade, Science and Governance),金明、王之光譯。香港:商務,2016。[8]

- 《天下華人》(The Chinese Worldwide),廣州:廣東人民出版社,2016。

- 《更新中國:國家與新全球史》(Renewal: The Chinese State and the New Global History),黃濤譯。香港:商務,2017。

- 黃基明著,《王賡武談世界史:歐亞大陸與三大文明》(The Eurasian Core and its Edge: Dialogues with Wang Gungwu on the History of the World),劉懷昭譯。香港:香港中文大學出版社,2018。

- 《海外華人:從落葉歸根到追尋自我》(The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy),趙世玲譯。北京:北京師範大學出版社,2019。

[1] English titles for books without published translations are tentative and subject to change.

[2] This book is the new edition of Community and Nation: Essays on Southeast Asia and the Chinese (1981). It consists of eleven essays from the original volume, eight essays published since 1981, and three earlier writings.

[3] Eleven of the essays in this 18-essay volume appeared in Wang’s previous work, Community and Nation: China, Southeast Asia, and Australia (1992).

[4] A reissue of a collection of 16 essays previously published in the 1970s to 1990s.

[5] This essay collection is the revised edition of The Chineseness of China: Selected Essays (1991) and has been modified and shortened to appeal to a general audience.

[6] This book is the second edition of The Structure of Power in North China during the Five Dynasties (1967), originally Wang’s doctoral dissertation at the University of London.

[7] This volume is a collection of seven papers previously published in Southeast Asia and the Chinese (《東南亞與華人:王賡武教授論文選集》, 1987) and seven new papers written in recent years to investigate new issues, trends and developments in China and overseas Chinese.

[8] There’s a simplified Chinese translation under a different title. See《1800年以來的中英碰撞:戰爭、貿易、科學及治理》,杭州:浙江人民出版社,2015。